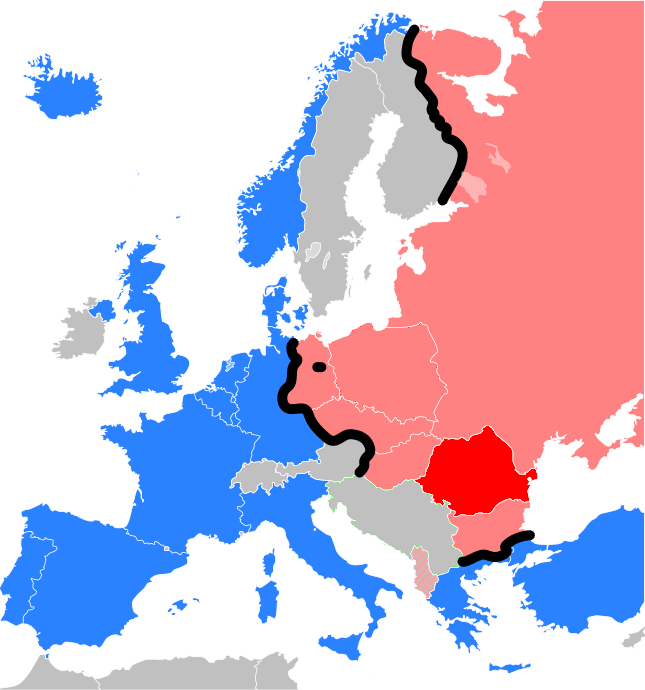

Following a growing interest in Europe’s Cold War Heritage, the Heritage Tribune is highlighting new perspectives from countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In three special articles written by three young authors, this heritage, which has become even more topical due to the war in Ukraine, will be described. How does the post-Cold War generation look at this heritage in Poland, Georgia, and Romania?

The initiative for these articles stems from the European Cold War Heritage Network and the Cold War Heritage project of the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency. The articles are also published in the Dutch Erfgoedstem Newsletter (Voice of Heritage).

Romania

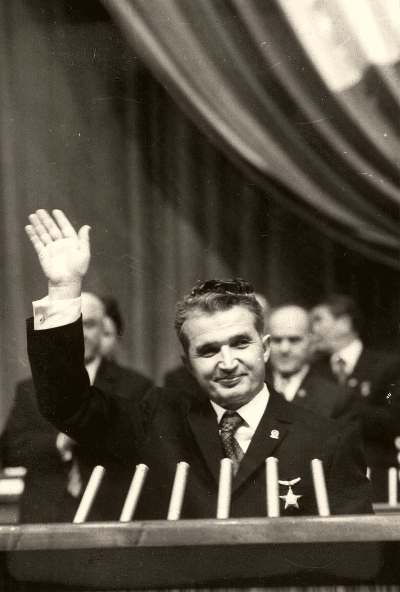

Romania’s communist era has been rather atypical for the region of Eastern Europe, whether the matter is dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s condemnation of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in the Spring of 1968 (making Romania the only country from the Warsaw Treaty Organisation to stand against this act) or the way the communist regime ended (through the execution of Ceaușescu and his wife – a bloody ending, unlike the peaceful ones seen in neighbouring countries).

Although Romania had seen its fair share of influence from the Soviet Union, the Soviets retreated their troops from Romania in 1958, perhaps because Romania had shown allegiance after the Hungarian Revolution. Whilst it was not Soviet, Romanians nevertheless lived under a socialist regime.

Following the revolution against Ceaușescu in 1989, Romanians embarked on a quest to deny their very own recent past. Before the revolution had been the most severe years of the communist regime, during which people were deprived of basic utilities (electricity was severely rationed, for example) and everyone had to queue up for hours in front of grocery stores, often only to come back home empty. Now, when Romanians think of the buildings and objects of this period, it is in no way positive. Codruța Pohrib, a Romanian scholar, remarks that the memories are “tantamount to the prison cell, the squalid apartment building, the inedible or scarce food”.

This extremely negative association that certain generations of Romanians experience towards the communist era has been passed on in various forms to the younger generation. Young people today experience tangible evidence of this past on a daily basis – such as Plattenbau-style apartment blocks and chaotic cities resulting from the demolitions initiated by communists – but the Romanian youth often struggles to understand this tormented past.

At the same time, due to the fact that the peak of the Cold War tensions in the 1980s took place at the same time as the harshest oppressions of the communist regime, our memory tends to focus only on the consequences of the regime. The tangible elements which would remind people of the Cold War are not in plain sight, which further disrupts the remembrance process. In Hunedoara county, for example, the traces are in the form of anti-atomic bunkers. Meanwhile, the village of Vadu Dobrii bears an abandoned military base believed to have been built at the end of the 1950s. Since the village is rather secluded and has less than 10 inhabitants, its presence in the common memory is negligible.

The House of the People (currently the Palace of Parliament), Bucharest’s most monumental construction erected during the 1980s, features an impressive anti-atomic bunker. Although many parts of the building are accessible to visitors, the bunkers are still out of reach from the tourist gaze. Furthermore, the apartment blocks built starting with the 1970s had dedicated underground shelters in case of conflict, but these have since been transformed into household storage spaces.

It can be therefore said the heritage of the Cold War era has been somehow enveloped by the overall heritage of the communist years, and that the shared conscience in Romania does not separate the two eras when it thinks back to those decades. There was always a certain awareness, but it was always kept out of mind, overwhelmed by the everyday conditions of the regime. For Romanians, Cold War heritage is communist heritage.

A prominent recent theory in heritage is that there has been an increasing collection of heritage places or objects, which might restrict the process of actively creating new memories. Whilst remembrance also involves forgetting, perhaps it is worth discussing just how much we allow ourselves to forget before we lose our sense of the past. In addition, it is also worth questioning whether the younger generation can interpret the past in their own way if they are denied its very legacy in the first place. This would include approaching both the communist era as a whole and looking at what the Cold War was like on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Perhaps there could be a dialogue between the Western imagination of the concept and what people in the East actually experienced.

I feel that the country is still lurching between denial and anger

There is a famous model of experiencing grief, which suggests five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I feel that it also can be applied to Romania’s transition from a communist regime to a democracy. Currently, I feel that the country is still lurching between denial and anger.

While, of course, the grief process is rarely a linear process, Romania is yet to find its acceptance for what it experienced – an acceptance that would need to be internalised. This would not only justify and legitimise certain aspects of the past, but also gain closure and finally propel Romania forward.

The Cold War is not really on the minds of today’s Romanian youth. Not only is it hidden, but it is overshadowed by the immediate sufferings of the communist years. There was too much going on at home to worry about what the West was doing.

Miruna Găman

Miruna, 29, is a Europa Nostra/ESACH trainee, a project manager at the ARCHÉ Association and a PhD student at the University of Bucharest