Over the last decades, the concept of sustainability has been the object of a rising interest given its conception as a progressive response to the environmental and social difficulties faced by our societies. However, the general attention was seemingly focused primarily on green, innovative and high-tech solutions in the attempt to cope with the problem. As a result, new globalized morphologies derived from technological advancements tend to replace the local forms of our cities and, in this view, the general impression is that sustainability means the opposite of heritage and that we need to put aside our past to move towards innovation and economic growth. With that being said, is there another conception of sustainability to be put forth? Can we mix innovation and high technology with our traditions and heritage? Can we applied them to the renewal of our built environment without loosing its peculiar values or freezing them through conventional projects of museum reconversion? It is in this context that advancements in the modelling of Smart Cities may offer some valuable insights.

Written by: Federico Varela Mazzantini.

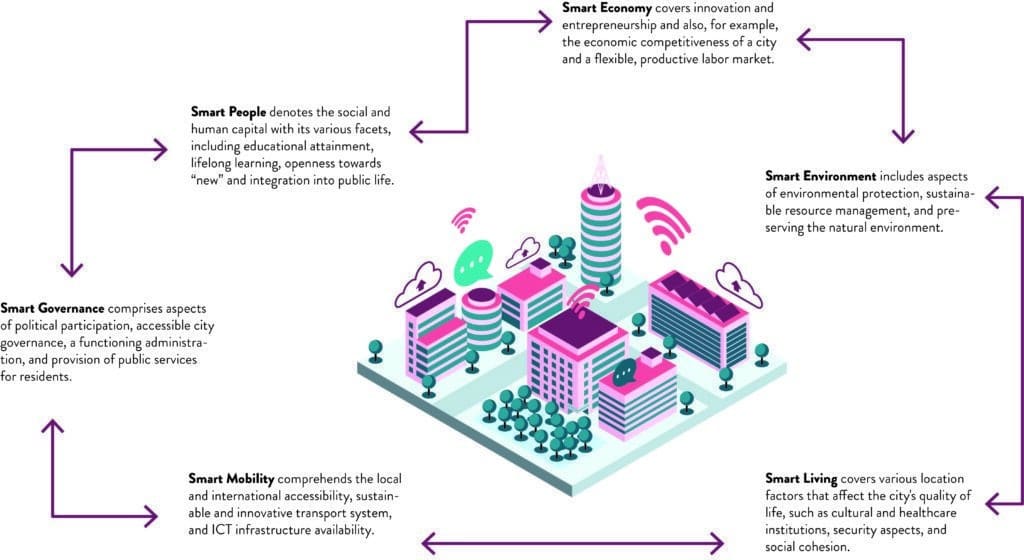

Specifically, the term is used when the latest technological innovations are used in urban infrastructure to support the needs of public institutions, businesses and citizens to work together as a common functional organism. The core idea of a Smart City model is that of employing technological advancements to implement via information systems processes which optimize the urban system components and tighten the contact between citizens and public institutions. To be developed efficiently, this organization must therefore function in different areas of city life, such as in the operative areas of transport infrastructure, but also in the economic, cultural and environmental spheres.

Greenfield projects

Smart Cities schemes can be on the whole divided into two main categories: “Greenfield” projects, that is to say new cities, and “Retrofitting” of existing built fabrics.

Greenfields comprise Smart City projects where urban schemes are designed from scratch on vacant areas. Similar projects allow the innovating planning vision of a Smart City to become a reality, and they present themselves with some common features. First, they emphasize environmental sustainability through the installation of intelligently networked infrastructure systems, the use of renewable energy sources, and energy-efficient architectures. Second, a predominant characteristic is their being strategically located near existing airports or metropolitan areas, which is a typical approach of some Arab and Asian countries due to the recent economic development of the regions. The most distinguished examples of similar cities are Neom city in Saudi Arabia and New Songdo City in South Korea.

Retrofitting

Conversely, most European cities share the characteristic of having an economic and social education level stable and high enough to permit reflections on how to improve the quality of life of all their inhabitants. The idea of intervening on existing settlements is therefore a common goal in most of Europe and this strategy is referred to as “retrofitting”. Contrasting the general conception of a smart city as a large scale urban proposition informed by high-tech advancements, parallel strategies for the retrofitting of entire districts or even individual buildings have been advanced on the micro-scale and these may in fact be conceived as an initial step towards a disparate yet likewise innovative smart city model.

Innovation Districts in particular, being these the fusion between industrial districts and research parks, seem to address the topic of transforming a city into a smart one in a progressive way. Due to the renewal and development of cities, the areas where the former industrial districts were located remained in most cases as residual spaces with low income flows increasingly detached from the general urban fabric. Research companies trying to relocate in these remnant areas for convenience surely change their appearance, but also expand the possibility of intertwining high-tech research companies with start-ups and new investments that were not previously considered.

Innovation Districts allow for deep and homogenized linkages between residential, commercial, technological, and cultural areas. The main reason for this is that Innovation Districts always tend to develop from small and concentrated spots which is what allows them to establish connections with the consolidated urban fabric in the surrounding areas.

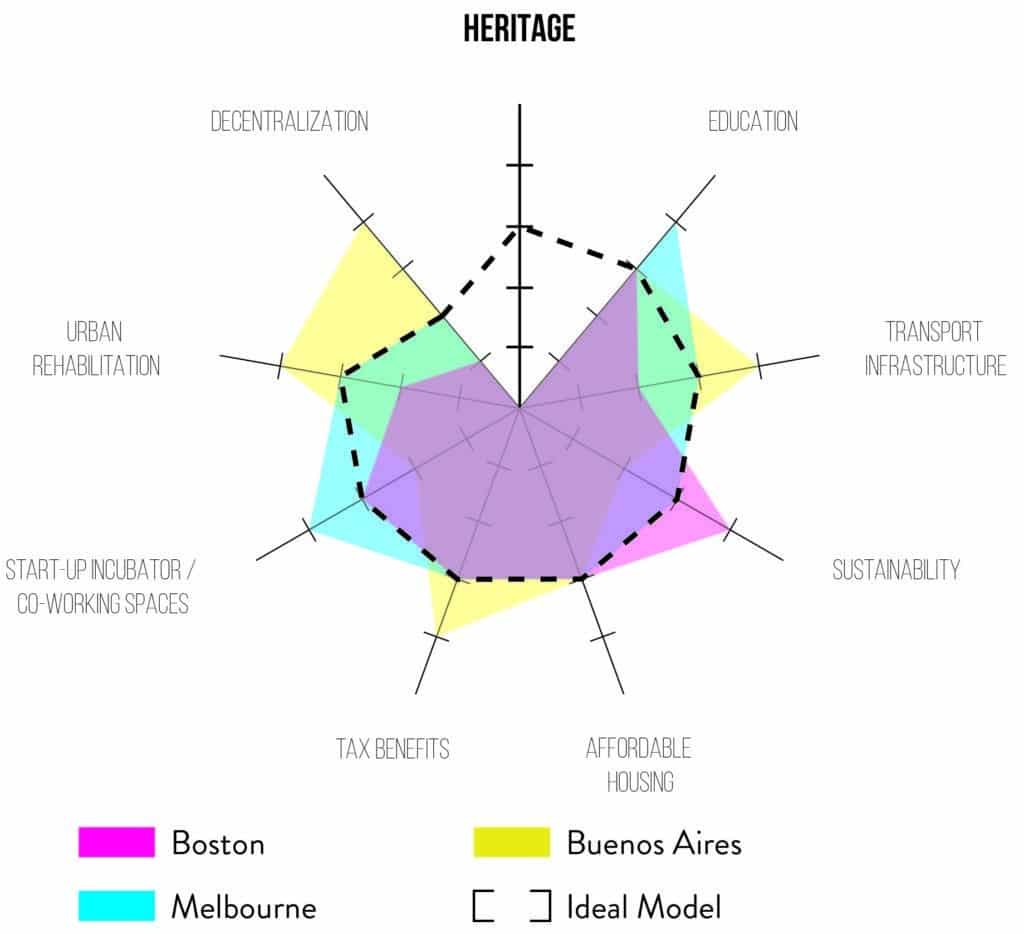

Successful cases such as the Technological District of Buenos Aires, the South Waterfront District of Boston and MID City North of Melbourne prove that innovation districts could be a sustainable answer to urban transformation of neglected contemporary urban areas. These examples helped to homogenize these cities’ population distribution, encouraging the use of mass transportation instead of private vehicles, increasing the land value by including green areas and the most crucial, fomenting innovation to develop new technologies that would help to achieve a better and more sustainable way of living. However, a key aspect not considered in many cases is the local residents’ interests to maintain the essence of their traditional urban environment. Relating community representatives to project-related stakeholders may in fact lead to a higher and shared understanding of the place characteristics, resulting in a long-term process that may sustain itself through participation schemes defined in the project dimension, but prospectively renovated through the community engagement.

On top of this, is there a way to increase investment in heritage and incorporate the values of the historic sites that are being transformed into the new vision of urban life proposed by Retrofitting Smart Cities? What if we deviate from the recurrently witnessed museum conversion and start to think of applying different business models such as innovation districts, or even grassroots activities such as a restaurant?

Building interventions

In this respect, in the historic Mayfair district in London, a deconsecrated church remained neglected and hidden from public view for decades and its recent reuse offers a valuable example. In 2016, the group Mercato Metropolitano invested 5 million £ to restore and repurpose this beautiful historic building as a street food hall and reopen the site to the local community. Not only did this intervention revitalize an undervalued yet creditable building, but its program went on in proposing community spaces fully open to residents as well as clubs dedicated to local events.

Another successful and unusual example of a deconsecrated church reconversion is San Paolo Converso in Milan. Originally built in 1631 and purchased by the architectural firm Locatelli Partners to house its studio, the church consists of two main bodies. The part behind the altar, originally used for the seclusion of the nuns, nowadays houses an imposing glass and iron structure that contains the studio offices and transforms the crypt into a “table of ideas”. On the other side, the part in front of the altar is a space entirely dedicated to art, where the Converso cultural association organizes exhibitions, events and performances. In 2017 for instance, the artist Asad Raza transformed this interior into a tennis court intending to explore the way in which people use spaces through social practices.

A different approach

These successful examples of disruptive reuse programs show that there may be other ways to preserve our historic buildings. Ways that as a matter of fact would mean a reduction in governments’ conservation expenditure, deviating their role to act as supervisor or co-manager alongside private sector investors that would restore and renovate our heritage in exchange for business opportunities . As a result, a diversified economy could flourish, bringing an increase in business and profits for both residents and small, medium and large companies, reflexively resulting in an overall increase in governmental revenues without a direct action of public institutions.

Instead of the green, innovative and high-tech solutions that have changed the autochthonous appearance of cities transforming them in globalized morphologies, sustainability finds its way in different schemes that allow for the blending of high technology innovation and economic growth, with the cities´ traditions and heritage: Smart cities, Innovation Districts or the reuse of heritage. The imaginative reusing of historical sites needs thus not be deemed heretical but beneficial since it is a way to preserve and maintain a society’s past. In these cases, by applying innovative business models in heritage sites, sustainability also means preserving the historical buildings while extending their life expectancy and carrying on their significance.

About the author

Federico Varela Mazzantini is an Argentinean-Italian architect who currently lives in Oslo, Norway. He specializes in the management of the cultural heritage that could revitalize communities through interventions in neglected architecture. For this reason he is part of the organization International Center for the Conservation of Patrimony (CICOP). He had the opportunity to become a professor at the University of Buenos Aires (FADU) in the subjects History of Architecture and Design. At the same time he worked as Project Manager & Facilities Managers for public institutions and companies such as CBRE and S&P Global. He studied architecture at the University of Buenos Aires. He then deepened his knowledge with a full scholarship at the Politecnico di Milano in the Architectural Design and History Master. He is passionate about sketching, he believes that this is the best way to transmit his thoughts. For this reason he ran Urban Sketching Workshops in Milan, and now he is starting these workshops in Oslo, complementing his architectural career.

- Email: varelafe@gmail.com

- LinkedIn: Federico Varela Mazzantini

- Instagram: @Varelafe