This article is a reflection on the role of communities in promoting and preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH), through the lens of the HIPAMS (Heritage Sensitive Intellectual Property and Marketing Strategies) India project. It is largely based on the toolkit developed by HIPAMS India, which is licensed under a CC-BY-NC license. Here, you will find you an overview of:

• The HIPAMS project and process;

• The process of co-creation with communities;

• Examples of some tools;

• Community experiences of implementing the strategies.

Written by: Kavya Iyer Ramalingam.

Project and process

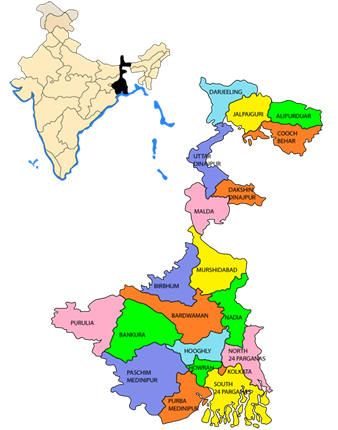

The HIPAMS India project was launched in 2018 to develop heritage-sensitive commercialisation strategies with ICH communities in West Bengal (India) to support local stewardship in the global market. Community artists, an Indian NGO working on sustainable development through heritage, and an academic team based in Europe are co-creating these strategies, working at the intersection of ICH, marketing and IPR (intellectual property rights). It is still a work in progress, hence, all methods and results are still being tried and tested.

However, the three main ideas which form the bedrock of this project are well defined:

- Intangible cultural heritage management (or safeguarding) should be done primarily by the communities and groups that practise and transmit it. Where they require the assistance of others, solutions should be co-created.

- Commercialisation of products created through ICH practice can promote sustainable development and benefit the communities concerned, if mitigations are in place to reduce associated risks. With respect to heritage and the markets, the risks of over-commercialisation and excessive tourism have been widely established, born primarily from the tension between ‘sacred’ heritage and ‘profane’ commerce. Conversely, the problem of under-commercialisation, which could threaten artists’ survival and the preservation of heritage skills, has been grossly neglected.

- Intellectual property and marketing strategies can support heritage safeguarding in developing countries if attention is paid to what is protected or promoted, by what means, and under whose control.

Co-creation with communities

The project strategies have been developed and tested with stakeholders from Patachitra, Purulia Chhau and Baul communities in West Bengal, India. Respectively, Patachitra is a special technique of painting stories on cloth-based scrolls accompanied by songs as they are unfurled; Chhau is a vibrant, folk dance-drama form arising out of martial practices; and Baul is a musical tradition as well as a philosophy, propagated by mystic minstrels.

In particular, the HIPAMS model is rooted in community empowerment, heritage skills repertoire, reputation, and heritage-sensitive innovation. It tries to offer a new perspective on community engagement and ICH by following a four-step process of diagnosis, strategy development, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation.

At each step, the very process is questioned in manifold ways. For instance, how can artist communities most effectively promote and protect their reputation as custodians of ICH as well as raise awareness about their art? How can they balance safeguarding heritage skills while innovating to reach new markets? Also, how can they identify and protect their commercial rights and gain more control over their work with regard to third party use?

The roots and fruits model

One of the examples of the tools used is the roots and fruits model [represented in figure 3]. This helps artists visualise the relationships between heritage products and services, and the roots of the traditions they depend on. For the Patachitra community of painters, roots, for example, could include making scrolls out of paper pasted onto sari (a traditional women’s garment worn in India), making and using natural paint colours or composing songs and stories based on Patachitra heritage [figure 4].

On the other hand, fruits could include new products such as painted bamboo, terracotta, wood, glass, leather, painted kettles, umbrellas, hand fans, mats, books, graphic novels or new kinds of performances, songs and themes. But also products closer to the roots such as traditional long scroll with singing, traditional square scroll or traditional tunes and lyrics.

The roots and fruits model has proven to be beneficial in helping the communities identify which aspects of traditions may be suitable for commercialization, and which, not. With this in view, the tool has been used by the communities in two cases.

The first is that of specialized HIPAMS scrolls. The communities themselves designed scrolls such as those explaining IP rights or geographical indications [figure 5]. These have been particularly useful for disseminating information amongst other artists, but also consumers and other organisations.

The second case concerns packaging options [figures 6a and 6b] for Bengal Patachitra scrolls and diversified products such as t-shirts, kettles and postcards, which have been recently conceptualized and designed by the community of Patachitra artists in Pingla. The containers have QR codes printed on them which direct users to the website co-created and managed by the community. The website has links to performances of paater gaan, which are songs traditionally sung by the Patuas while unfurling the scroll. The packages also have the GI logo printed on them which serves as a unique certification mark.

Community feedback and experiences

In conclusion, some of the early feedback and findings that have been reported by the community have been encouraging. Artists appreciate an improvement in their rights awareness and in their negotiation skills, with respect to both marketing and use of IPR strategies. An indicator of this is the fact that applications for GI registrations by individual artists have increased. Artists have also started effectively using digital tools for collective and individual promotion [figure 7], with many of them starting to engage themselves in online heritage education. In addition, the newly developed packaging has been appreciated by both customers and artists.

These observations and evaluations will be constantly revisited to help streamline future initiatives, and to empower traditional ICH holders. Eventually, this will enable them to have full control over their work while also sustaining their heritage and livelihood.

Source: Facebook – Video by Sonali Chitrakar

About the author

Originally from Kolkata, India, Kavya is currently a dance researcher, teacher, choreographer and performer in Paris, France. She graduated from Choreomundus – International Master in Dance Heritage, Practice, and Knowledge in September 2020. She has a multidisciplinary background in dance, heritage, education, economics and international development. She is passionate about participatory research, community-driven initiatives, and intersections between academic and corporeal practices. She believes that the arts and heritage sector can be great drivers of social change.

- Email: kavya.iyer93@gmail.com

- Instagram: @kavya.ir