Unrest among heritage crafts professionals, as the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) opened a public consultation on adding lead metal to the ‘Authorisation List’. If the metal is added to the list, it would mean that any company handling lead would need authorisation from the ECHA because of safety concerns. As lead metal is a key component of many heritage buildings and artefacts, the ban would have large consequences for the heritage sector.

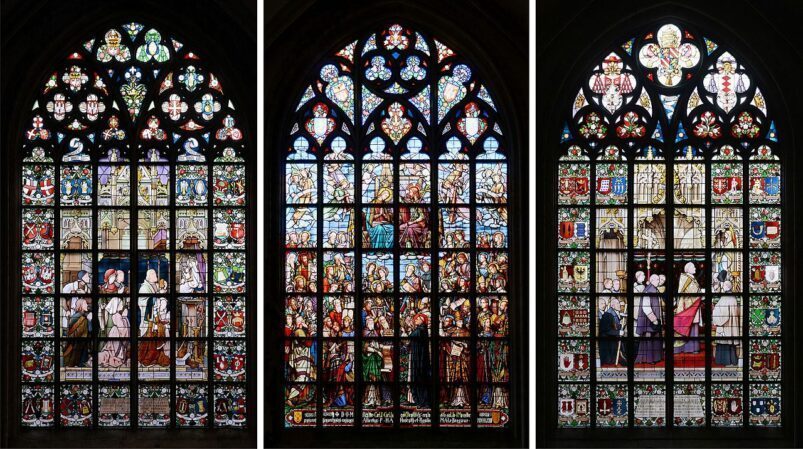

In response to this proposal, a joint statement was presented by ICOMOS, ICOM, E.C.C.O, ICOMOS-Corpus Vitrearum ISCCSG and ICOM-Glass. In short, the statement outlines the diverse range of uses that lead has in heritage and conservation. Many objects in museums are made of lead, painting conservation requires lead pigments, and there are countless cathedrals and heritage buildings with stained glass – of which lead is a fundamental component. Naturally, it would be expected that heritage uses would be excluded from this type of restriction, but it doesn’t seem to be the case.

The point of the law

The aim of the Authorisation List is to almost entirely remove dangerous substances from our society. It is intended to be a strong ban, where any use of the material is strictly controlled. In 2018, lead was added to the ‘Substance of Very High Concern’ (SVHC) list. When they opened up this to public consultation, nearly 200 pages of comments were made. However, as the agency was keen to point out at the time, the SVHC list does not mean that the metal is banned.

Many of the agency’s responses to the public at this time were “In a sustainable circular economy, substances of very high concern need to be phased out.”

Only a few companies pointed out the lack of alternatives to using lead for heritage purposes in 2018, whereas the new proposal has generated more concerns from the sector. Such an inclusion is remarkable- trying to phase out an entire metal from society is highly ambitious, and raises questions about how the agency will manage exceptions and authorisations.

Why does lead matter to heritage?

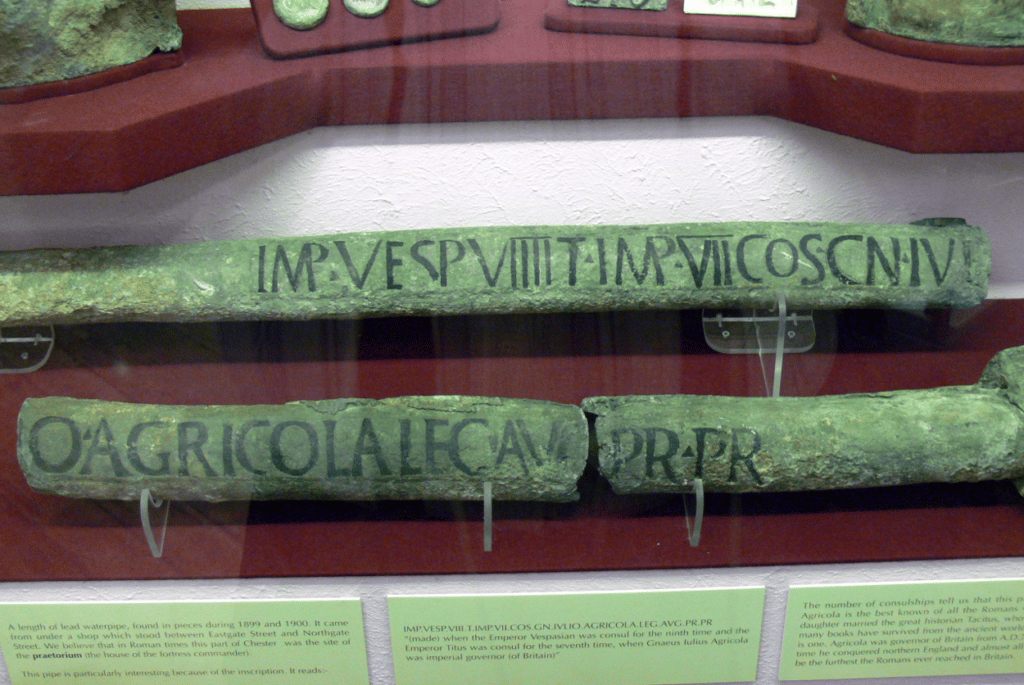

Lead is used in many things and has been very useful for people in the past. Its low melting point, high density, resistance to corrosion, and many other characteristics have given the metal a wide range of uses for centuries. The joint statement from ICOMOS and other organisations indicates that a range of heritage industries require lead – from classical stonemasonry to organ building. Similarly, many significant heritage buildings in Europe have lead metal in their construction, especially in stained glass.

neither the manufacture, nor the conservation, nor the storage or presentation … would any longer be possible without a special permit

The International Scientific Committee for the Restoration and Conservation of Stained Glass

The International Scientific Committee for the Restoration and Conservation of Stained Glass, is one of the bodies objecting to the proposal.

The committee said: “In the case of new or historic stained glass and leaded glass, this means that neither the manufacture, nor the conservation, nor the storage or presentation, e.g. in a museum, would any longer be possible without a special permit. While the UK may no longer be a member of the EU, this action would undoubtedly have a major impact far beyond the borders of the European Union.”

If the proposal goes forward, museums and heritage sites that handle any lead per year could need to apply for authorisation from the ECHA.

How serious would a ban be for cultural heritage?

It’s difficult to know – such a wide ban has not happened before. Most of the items on the Authorisation List are complex chemicals that are mainly used in industrial processes.

An exemption can be made for materials that are being handled with great care and safety procedures. The joint statement points out that safety regulations already exist for handling lead. Glass designers, fabricators and conservators/restorers are well aware of the toxicity of lead. There is protocol in place to manage the dangers, such as regular blood testing, the use of extraction systems with appropriate filters, and proper PPE. Those working in the profession work safely currently and the risk is well mitigated.

For scientific research and development, there is also no need to apply for authorisation so long as the amount is less than 1 tonne per year. For historic conservation purposes, a similar exemption would be ideal, as this would allow most museums and heritage sites to continue handling small quantities of lead.

What might be a concern is the supply chain. Anyone who would need larger quantities of lead for conservation and restoration would be forced to turn to large companies having the required permit. Conservation is already expensive, and this would undoubtedly increase costs and add impractical bureaucratic barriers.

There is precedent for repairing things that require restricted materials. For example, Lead Chromate (a pigment) is already on the Authorisation List, and thus requires a permit to handle. However, there is an additional 8 years to gain this permit if:

a) the original object was made with the pigment

b) it can only be repaired with that pigment

This means that conservators have a lot more time to either find solutions or make an application for authorisation. This is not a perfect solution, but a solution nonetheless. Historic objects have clearly yet to be considered by the ECHA, despite their socio-economic importance.

Within the heritage sector, there needs to be awareness of these proposals in the future. To continue using lead as a conservation and heritage material can be authorised – if an application is approved. It’s hard to see the EHCA turning down an application for Cologne Cathedral to preserve its roof with lead, but it’s worrying that such an obvious case isn’t already clearly exempt, or at least considered. Heritage needs a greater voice in these matters.

Unnecessary legislation

The ECHA needs to revise its proposal and begin to understand the deep history of the use that some substances have. Lead is undoubtedly a dangerous substance, but this particular proposal may have unintended consequences. If we want to preserve our heritage for a circular economy, we have to live with dangerous materials rather than just push them away.

The public consultation for the proposal ended in early May, so it is important to keep an eye out for the results. In the long term, heritage organisations may have to come together to show the ECHA the risks of its current approach.

Source: ICOMOS

Update: The 1 tonne exception is only for research and scientific purposes, the scope of which does not currently appear to extent to heritage and museum sites.