Long before humans entered Europe, landscapes were formed and altered by large mammals such as elephants. Ever since humans started to accommodate landscapes for their use, natural species have struggled to adapt. Could studies of pre-human Europe provide information and incentives to stop the current decline of biodiversity?

Written by: Teun van den Ende.

“Let’s hope there won’t be another Ice age soon”, a reporter from a local radio station on the Finnish island of Åland remarks. He is interviewing Dutch artist Bart Eysink Smeets on his initiative to ‘bring home’ a large stone that originated from the island and was deposited in the Dutch province of Drenthe in the penultimate Glacial period, roughly 200,000 years ago. According to the artist “nature has been moving for millions of years without humans being there at all. Since human beings arrived, they have been interfering with everything.”

Although the initiative is rather ‘gimmicky’, it also seriously questions the way we interpret the origins and management of European landscapes nowadays. A field of academic research is devoted to this question, explains Elena Pearce, a PhD-researcher in the TerraNova program, based in the Center for Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World in Aarhus, Denmark. She is studying the build-up of European landscapes in two different periods in history. “To people who ask me if the aim of my research is to recreate the past, I answer: no, we live in a different time. There are so many positives to humanity. But in order to make those positives enhance biodiversity, we need to study the past.”

Deep history

By examining Europe’s deep history, Pearce is learning how species coexisted in these landscapes long before Homo Sapiens took over. She is looking into the Eemian Period (130,000 – 115,000 years B.C.) – “a time in which large mammals such as elephants created big disturbances, lifting up the earth, knocking down trees.” The other period she is studying is the early Holocene, just before the start of agriculture, approximately 14,000 – 8,000 years B.C. She refers to both periods as natural baselines, that both provide a context for resilient and really diverse landscapes.

How that might work out in practice, is Arnout-Jan Rossenaar’s field of work. He is experienced in managing different types of landscapes at Staatsbosbeheer, the state-owned land management and conservation organization in the Netherlands. Rossenaar: “At the end of the last Ice Age the Netherlands was a polar desert, similar to the islands of Spitsbergen (in the Barents Sea, to the north of Norway, red.). The low-lying parts of the country were completely bare, resembling a sort of savanna. In the more forested areas mammals foraged and created large clearings. River landscapes flooded regularly and remained open for at least ten years before trees and bushes returned.”

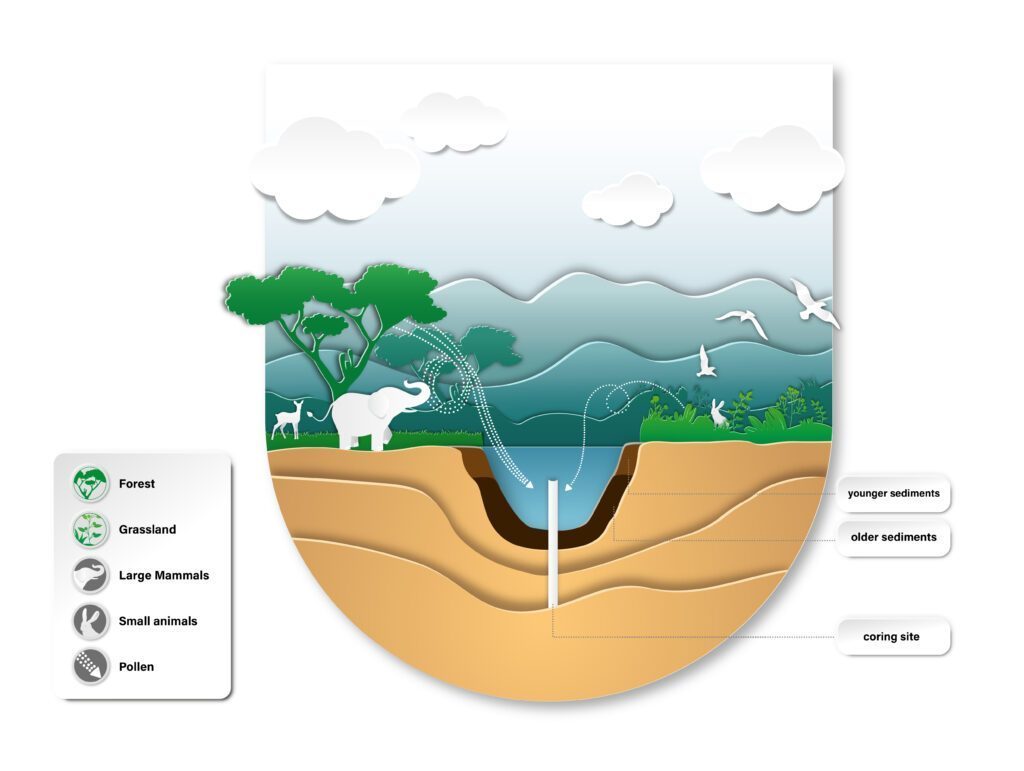

Academic studies on biodiversity support the idea that landscapes continuously changed in appearance throughout history. Pearce explains how we have gained access to this historical information: “It involves drilling into the earth meters below ground level, to uncover pollen records that have remained preserved for thousands of years. It tells you which plant species used to exist in a certain place.”

Research based on previous studies of pollen records has, however, proved unreliable. But scientific methods are becoming more advanced, argues Pearce: “Trees like birch, elm, alder and ash were overrepresented because they produce far more pollen than others. Recently developed models take in new data that accounts for differences in pollen productivity and dispersal. These models allow more precise reconstructions of the landscape and the species that existed in it.”

Increasing biodiversity

The historical information could be taken into account to inform decisions on the future management and design of landscapes, but Pearce isn’t convinced that is happening. What she does observe is a focus on large-scale tree planting initiatives, that she questions: “The picture that is often painted of Europe as one large forest is a romanticised one and is perhaps based on folklore. Tree planting might be effective in offsetting carbon emissions but also create homogenous landscapes with limited biodiversity.”

Pearce’s problem with this approach, and other traditional conservation strategies, is that it creates homogenous habitats that fail to create biodiversity. “They say: we want moorland so we’re going to burn it every time it gets too overgrown – or – we have one rare type of species that we need to keep, so we’re going to make the landscape accommodate it.” She thinks this desire to control our natural environment is what’s actually causing the current biodiversity crisis. “We shouldn’t be so caught up with preserving a fixed state. Instead, we should focus on creating heterogeneous, dynamic and self-sustaining environments.”

Her point is backed up by historical research. They show that pre-human European landscapes used to be very diverse, a mix of open grasslands, scrub, heathland, and patches of forest. “These landscapes relied heavily on large animals that continuously created disturbances and clearings. By understanding the dynamics of these landscapes, we could again create resilient ecosystems where many different species can thrive.”

Rossenaar has seen biodiversity increase due to human intervention. The Dutch ‘Room for the River’-program, set up to prevent rivers from flooding the vulnerable delta, also focused only creating ‘new nature’ in the rivers’ floodplains. As a result, several plant and animal species have been reintroduced. Most notably, storks have returned to areas such as the Biesbosch and IJssel-valley after becoming extinct in the Netherlands in the 1970’s. “This shows how landscape design can play a major role in creating biodiversity if it takes ecology into account. It also shows that ecologists, who sometimes get stuck in their own baselines, can learn from landscape architects”, Rossenaar argues.

Shifting baseline syndrome

Stork sightings might have triggered childhood memories with older Dutch citizens, whereas youngsters had never seen one before. What we think is a normal state of nature is judged by most people according to the condition of the natural environment in their youth. This point of reference creates a personal historical baseline and is generally thought to be established in the formative period, between 6 and 10 years of age.

The effects of this phenomenon on nature are known as shifting baseline syndrome. Scientists Soga & Gaston argue that this originates from the lack of information or experience of past conditions in an article published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment in 2018: “Consequences of shifting baseline syndrome include an increased tolerance for progressive environmental degradation, changes in people’s expectations as to what is a desirable state of the natural environment i.e. one that is worth protecting.”

The gradual decline in biodiversity that is taking place without people noticing, or objecting to it, has made Pearce think about what she could do to change it. Before pursuing her current academic career, she used to be a school teacher. She also worked at primary school level and regularly took the kids outside to teach them about insects and plants. “I would love to go back into schools. First of all, we need to start teaching about the biodiversity crisis – at the moment it’s not even part of the curriculum in Great Britain. That’s a really tragic thing, especially considering the youth strikes for climate, who are doing far more to raise awareness than adults are doing at the moment.”

Fig trees and kingfishers in Amsterdam

Rossenaar is also regularly confronted by indifferent attitudes towards the environment. Nonetheless, he remains optimistic. In his current job he works in woodlands and open peatland areas on the borders of Amsterdam, where many urban dwellers spend their leisure time. “Over the last decades, urban nature has become much more diverse than farmlands in the Netherlands. Urban dwellers are becoming more aware of nature. Some of them are also taking out tiles in the pavement to make tiny gardens in front of their homes. Others are creating greener gardens. I think that group is growing.”

Cities have successfully welcomed (back) species you might not expect there, Rossenaar argues: “The city is a great biotope, in part because it is a heat island where humans help to create biodiversity. For instance, fig trees have sprung up in over fifty places in Amsterdam, mostly close to Turkish shops. Why there? Because consumers buy figs there and spit out seeds between the bushes during their walk.” He is even more surprised by frequent sightings of Kingfishers in the heart of Amsterdam: “They generally tend to stay away from humans and therefore look for the quietest places, preferring to stay unnoticed. However, they now breed in all kinds of places including parks in the center of the city.”

Could human behavior really help to increase biodiversity? Pearce also knows some promising examples. Knepp stands out for her, a former commercial dairy farm that completely changed its strategy. “The farm made a loss for a long time, because they were farming on marginal land. Then they decided to sell their machinery and replace their cattle with deer, horses and Tamworth pigs (that are thought to have descended from wild boar, red.). That created a biodiverse and wild landscape with a multitude of species. Now they’re running a successful business in wildlife safaris and a campsite in the South of England, which is a pretty boring place in ecological terms! If it’s possible there, there is really no excuse for nature to not be everywhere. The story alludes to the common phrase: ‘if you build it, they will come’.”

Which societal challenges in the context of heritage, landscape and the built environment would you like us to address in our future articles? Please get in touch: @Future4Heritage on twitter or email

This article is part of a series ‘Future Making in the Anthropocene’ that focuses on imagining better-balanced future scenarios for European cities and landscapes, made possible by the generous support of the Creative Industries Fund NL.

TerraNova has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 813904.