For decades, cultural heritage institutions have been describing and cataloguing historical objects in their collections. However, this information is rarely updated to reflect changes in language and society, something which the newly launched project DE-BIAS is looking to change. But it’s not just a matter of picking and replacing terms, as the data has become part of our own view of the past.

Because societal narratives about history and the past are always evolving, the way we remember things does as well. The descriptions of monuments, objects and collections of today were often formulated in a time when society ignored and marginalised a wide range of people. Think for example of indigenous people, descendants of enslaved people, or members of the LGBTQIA+ community. In order to make museums and heritage collections more inclusive and accessible for all, an update is needed.

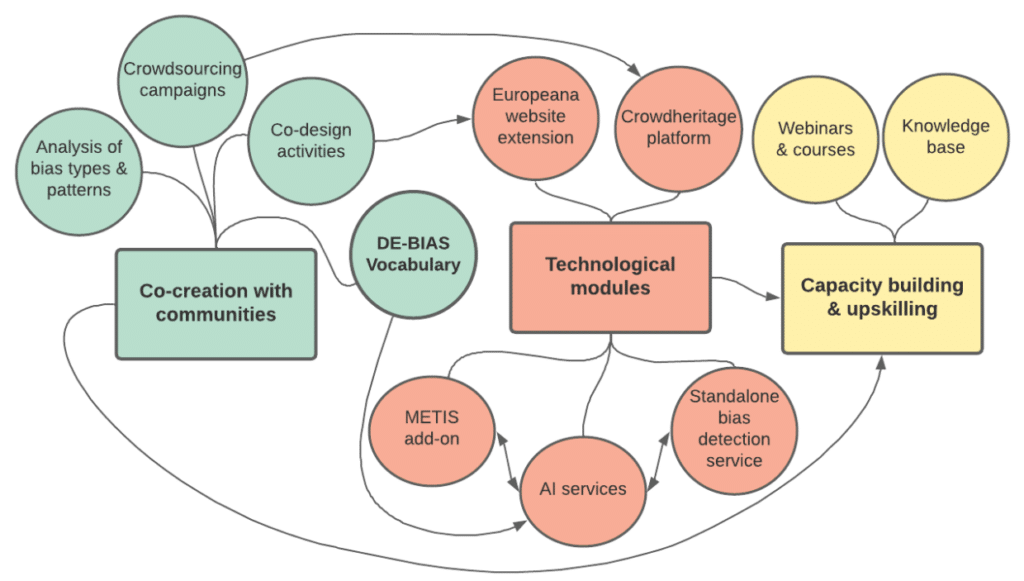

Hence why the DE-BIAS project aims to take on that exact challenge. By developing an AI tool to detect problematic terms in cultural heritage data and provide context on why it’s problematic, it aims to promote a more inclusive and respectful approach to the description of digital collections.

The project wants to work together with the marginalised communities ‘by giving them the space and agency to change the way that cultural artefacts have previously been described’, their website reads. A bottom-up focus to find out which words are problematic – and why – is key to creating a more inclusive collection and museum world.

The project will test their newly developed tools by analysing more than 4.5 million records currently published on Europeana, in five different European languages. Eventually, the tools should be available to interested cultural heritage organisations so that they can analyse and update their collections where needed, along with the required knowledge to do so.

The project consortium is composed by the Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum (coordinator), Europeana, Datoptro, European Fashion Heritage Association, Thinkcode, Michael Culture Association, Centro Europeo per l’Organizzazione e il Management Culturale, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Stichting Archives Portal Europe Foundation, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication and the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision. The project is co-funded under the Digital Europe Programme (DIGITAL) of the European Union. Follow the project hashtag #DeBias on social media to find out about the latest activities.

Raising Awareness

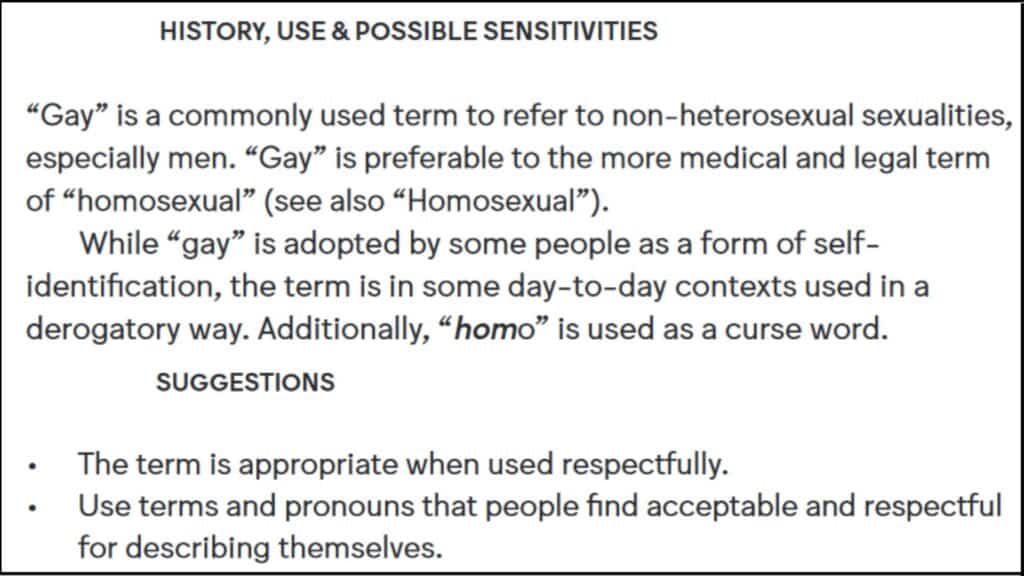

However, DE-BIAS is not the first attempt to deal with problematic terms. The National Museum of World Cultures in the Netherlands’ report ‘Words Matter. An Unfinished Guide to Word Choices in the Cultural Sector’ from 2018 is another example of an attempt to update terms in collections. It suggests a list of alternative words to potentially harmful terms. However, the document should ‘not be regarded as a clear-cut list of “bad” and “good” words’, museum director Stijn Schoonderwoerd explains. “It is to promote greater awareness within our sector of the meaning behind certain words, so our choices are more conscious and informed.” With the ultimate goal of making museums and their collections more accessible and inclusive.

Not long after, in 2019, the Amsterdam Museum decided to stop using the term Gouden Eeuw, or Golden Age, used to describe the 17th century when the Netherlands was at its pinnacle as a military and trading power. The museum replaced it with the use of ‘17th-century’. The term Gouden Eeuw does not do justice to those who were exploited during the era through forced labour and slavery, the museum explained their decision.

Replacing original terms

Nonetheless, simply swapping or banning a word from heritage collections brings its own challenges. How do you know which words are offensive or problematic if they’ve been in collections for such a long time? And what about the fact that they have been part of a collection for a long time, and that they have shaped our current views on the past as well?

In the same publication, collection manager Marijke Kunst explains how the museum deals with ‘replacing’ problematic words and the problem of replacing those words. “An object’s original title—on the (back of the) object itself, for example—is given in quotation marks. For the public interface, however, the museum has chosen a presentation title, which may be different from the titles on the catalogue card. While offensive words are not included in the presentation tile, the original titles are preserved in the database itself and thus remain accessible to the public.”

Tricky Process

In the end, DE-BIAS’ goal to update data and descriptions in heritage collections through AI tools appears to be the way to create a more accessible and inclusive museum and heritage sector. Especially if it’s done in cooperation with underrepresented communities.

However, replacing terms also creates a risk that the historic context of certain words that have shaped our view of the past is forgotten, as the Words Matter publication shows there are not necessarily ‘good’ or ‘bad’ words, but institutes need to build more knowledge about why certain terms can be regarded as problematic, and communicate this to the public. Updating collections doesn’t mean that historic terms are erased completely, the report shows. Preserving the original titles in databases or distinguishing between presentation and catalogue titles could contribute to creating an inclusive collection, without disregarding the past that shaped them.