Centred around the concept of ‘lifelong learning’, European citizens and companies are encouraged in 2023 to make the most out of the European Year of Skills. And while the EU’s focus is on training new professionals to complete the green and digital transitions, the heritage sector is also dealing with a ‘skill shortage’. What skills does the sector miss? And why is it so important to jump on it now?

So what is an European Year? “It’s an awareness campaign on a specific issue to encourage debate and dialogue in and between EU countries”, the EU website tells us. During such a year the EU puts additional funding into projects that address the thematic issue. These projects can be at a local, national and even cross-border level.

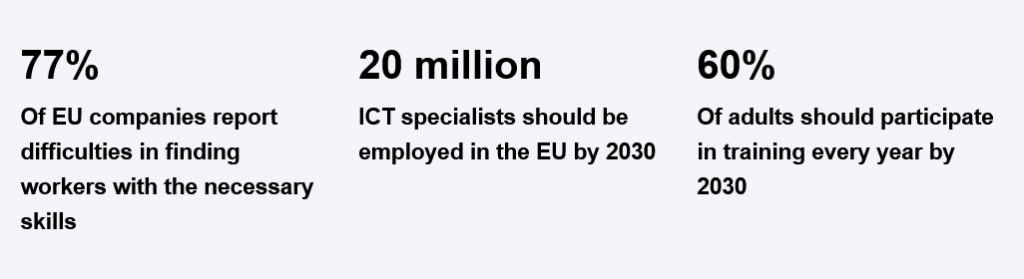

One of the reasons the EU decided to designate 2023 as the Year of Skill is to address the ‘skill shortage’ in the labour market. It should also fit the EU 2030 Social Targets, which means that at least 60% of adults follow training every year, and at least 78% of adults should have a job.

It’s definitely not a small sum the EU has put towards their ‘lifelong-learning’ campaign. Several existing EU funding bodies such as the European Social Fund Plus (€99B), the Digital Europe Programme (€580M) and Erasmus+ (€26.2B) have significant funds available for supporting people to become professional experts.

Shortages in the sector

The ‘skill shortage’ is also a problem in the heritage sector. One of the most noticeable problems is the shortage of experts in traditional heritage crafts, e.g. carpenters and glass blowers. In 2021 the UK’s Heritage Crafts Association listed 130 traditional crafts as endangered in their Red List of Endangered Crafts publication.

The key to building a healthy sector is to make sure those buildings and intangible traits survive. This includes not only upskilling or training current professionals, but also handing proper opportunities to young people to start careers in conservation, something the German Foundation for Monument Protection has been advocating for.

Academy approach

One of the initiatives that’d fit the EU’s idea of skill development is The European Heritage Academy, which started five years ago. Founded by the Burghauptmannschaft Österreich (BHO – an authority responsible for the administration and construction supervision of historic buildings in Austria) and the Austrian Bundesdenkmalamt (BDA). Its purpose is to offer certified, tailor-made training for specialists in the field of built cultural heritage.

It’s not really a surprise that the BHO is in need of skilled heritage professionals, who know their way around built heritage maintenance and conservation. But as the BHO tried to carry out its specialist service for built heritage, Burghauptmann Reinhold Sahl noticed that the organisation was missing something. “Training and further education, including knowledge management, were the central topics for me, and it soon became clear to me that it was also a question of personnel”, he explains.

“You have to imagine that we have permanent positions: if a staff member retires, I can only fill that position after that person has actually left. It then takes six to nine (!) months to get a new staff member. And then they need months for training.” By founding its own heritage school, the BHO can now train people for specific positions and tasks, making sure they have the exact skills for the job.

So far €3.2M have been invested in course modules that are now offered by The European Heritage Academy, creating 5 ECQA (European Certification & Qualification Association) certified course modules for professionals in built Cultural Heritage.

Soft skills

Another institute that focusses on skills needed in the sector is CHARTER, the European Cultural Heritage Skill Alliance. The Erasmus+ funded project, with a budget of €4M, started in January 2021 with the goal to research and put forward Cultural Heritage Actions to Refine Training, Education and Roles.

CHARTER is already trying to ‘upskill’ the sector. With publications and tools, such as the Skills Self-assessment Toolkit, on what skills and competencies are needed in the sector. And just like the ‘hard heritage skills’, handing opportunities to the next generation is an integral part of that: check out these interviews with young heritage professionals and what they have to say about what skills the sector needs.

Not only do people expect to recognize and understand heritage, there is a sense that they feel entitled to do so

Conor Newman

Apart from the ‘hard heritage skills’ – conservation, maintenance and craft knowledge – soft skills are also needed in the sector. Without the proper knowledge on how to communicate to the public what heritage is, and why it’s important, the sector will lose its relevance. Archaeologist Conor Newman argued this as well during CHARTER’s annual meeting that mediation and enablement will be the main skills needed for cultural heritage professionals in the future: “Not only do people expect to recognize and understand archaeological heritage, there is a sense that they feel entitled to do so (long before Faro I might add), or at least not to be excluded from it.”

“We’ve learned that heritage is personal, and therefore is accompanied by feelings of recognition, familiarity, ownership and belonging. Archaeology is, above all, local. And every time I say ‘archaeology’ you should substitute this with heritage or your own area of specialization.”

He reckons that the real goal is to inform and win the public over to the principles that shape practice in the sector, and “how well-thought-out ethics set the parameters of professional practice, including management of the public resource, and, importantly, why expertise matters. This means learning how to situate heritage values and practices.”

Training a sustainable sector

For the heritage sector, the Year of Skills should not only be a matter of training current heritage professionals. It’s also an excellent opportunity to build a more sustainable professional heritage sector.

Since especially built heritage is in need of conservators and craftspeople, more effort should go into pursuing the next generation and attracting them with good opportunities to make sure we have expert professionals that can step in when the current generation retires. Showing the public what the sector exactly does should be a crucial part of those areas of training.

And what better time than now? The knowledge from experienced professionals is (still) available and is now supplemented with significant funds from the Year of Skills. It’s only a matter of getting on with the training.