Since July 2022, the heritage sector can rely upon the independent Cultural Emergency Response (CER) for emergency assistance. And they pack plenty of experience since the organisation, based in Amsterdam, was founded back in 2003 by the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development in response to the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas and the looting of the Iraq Museum.

Since then, CER has developed into a major organisation that provides emergency assistance for heritage. Growing too big to operate within the structures of the Prins Claus Fund, they made the step to become an independent organisation. All the more reason to have a chat with director Sanne Letschert about the ins and outs of the ‘cultural heritage ambulance’.

How do you organise an emergency response for heritage?

When we hear that heritage is in danger, we do two things: firstly, we try to get an overview of the situation of the heritage in a region as quickly as possible. Secondly, we try to get a picture of the cultural and political context of that heritage. We contact local partners to help us with that; they have a better idea of what is needed and what are sensitive issues than we ever could.

Then we ask the question: ‘How can we help?’ Again, the partners on the ground advise us about what is needed, and what course of action we should take. We also start fundraising to make sure the plan can actually be implemented. Since CER was founded in 2003, we have been able to gather a loyal group of funders active in the heritage conservation sector.

We also tap into international organisations that have an interest in the field of culture or heritage, or in specific regions, for example, UNESCO, ICOM, etc. Based on the help we can get, we make an action plan. Together with civil actors and heritage institutions, but also engineers and architects we then organise several missions.

What kind of missions?

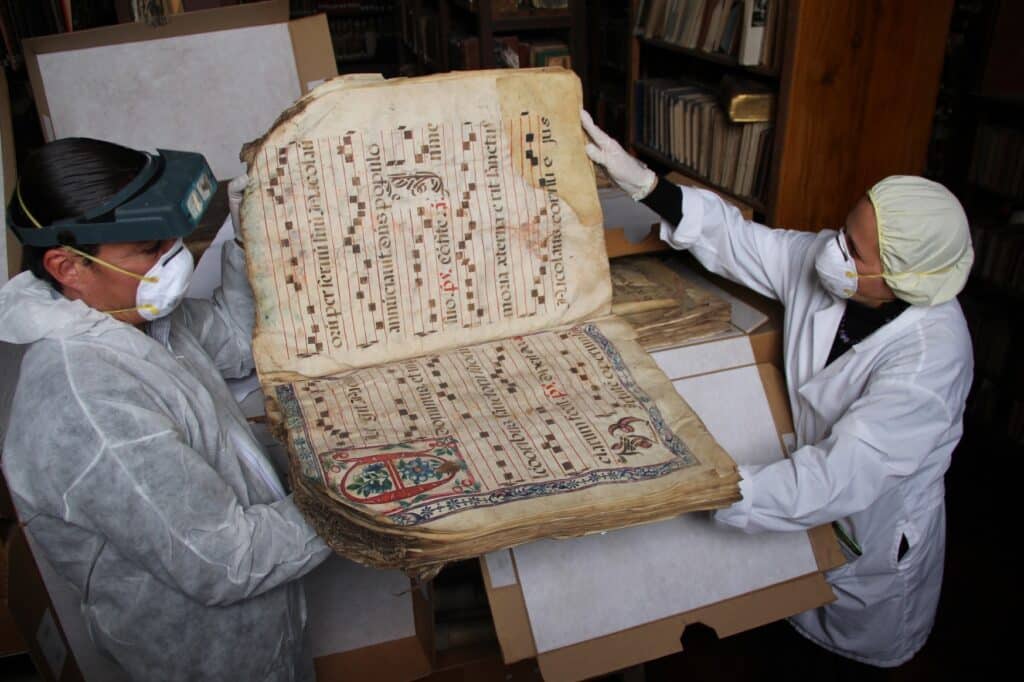

CER is a kind of ‘cultural ambulance’: we provide acute emergency assistance where needed. Think of evacuation of artefacts, covering damaged buildings, and preventing further damage. For example, last winter we noticed that organisations and museums in Ukraine we were already working with, encountered new problems. The cold and snow made it difficult to protect heritage in damaged buildings or to control the correct temperature for sensitive materials. That’s when we started coming up with emergency solutions to solve those problems.

And although we once started as a ‘cultural ambulance’, we do much more. We are also trying to raise the profile of heritage internationally. Especially when it comes to crisis response, culture is often a bit neglected.

How do you do that?

The other day I was at the NATO headquarters to talk about the importance of protecting heritage in crisis situations. We also keep in touch with humanitarian organisations like the Red Cross, and in the case of the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, Giro 555.

We want to make it clear that culture is a basic need for people, just like shelter and food. Therefore, activities such as restoring and rebuilding cultural heritage are crucial for people’s mental health and trauma processing.

What are you working on at the moment?

The past few days we have been incredibly busy with the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. It is a huge operation to ensure that heritage aid gets to the right place after such a disaster that affects such a massive area. But we have to make sure it remains workable for us as well. There is a lot of damage, but at the moment it is difficult to assess what is needed exactly.

So you are providing assistance in Turkey and Syria, but also in Ukraine. And there is a lot more heritage in emergency situations. How do you decide whether you will help?

That’s a good question, and almost impossible to answer. We try to determine whether it is manageable for us to coordinate help. That also has to do with our network. For instance, we have CER Regional Hubs in the Western Balkans, Central America, and the Levant region. And we are setting up a network in the Caribbean. Those hubs are partner organisations that we have known for some time, and who have often followed training programmes that we have set up with ICCROM and Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative.

To coordinate aid in Turkey and Syria, we have a lot of contact with our CER Regional Hub in the Levant, based in Lebanon. We hope to add several more hubs. But as you can see, we don’t have partners everywhere, so it’s a bit more difficult to set up an action plan for aid in certain areas. And, of course, we try to operate as neutral as possible.

What do you mean by neutral?

It’s a bit like the Red Cross: they are trying to help as many people in need as possible. With heritage, it’s more difficult, as it represents the identity and cultural values of certain groups. That means working with all parties involved or making the choice not to help.

Have you ever decided not to intervene or organise aid in an emergency situation?

During the Karabakh conflict in 2020 between Armenia and Azerbaijan, we made the decision to withdraw despite possible damage to heritage. The situation was so diffuse, making it difficult to come up with ways to respond to heritage emergencies, without escalating the conflict even further. However, we did release a heritage emergency response handbook and toolkit, translated into both languages.

Doesn’t it create a strange balance of power that Western organisations and funds provide assistance for emergency relief and restoration of non-Western heritage?

It is indeed quite tricky, and some power relations are hard to remove. This is precisely why the hubs were created. In an ideal world, the partners in the hubs tell us what we should do, because they know better than anyone else what specific needs are. This is ultimately what emergency response for heritage is all about: ensuring that the identity of communities is quickly restored and protected.

Cultural Emergency Response (CER) coordinates and supports locally-led protection of cultural heritage under threat. Cultural heritage is a crucial part of our individual and collective identities; it enriches our lives, connects us to our past and provides a foundation for our future. Culture makes us human, and the urgency of heritage protection is becoming increasingly clear. CER couldn’t do what it does without the support of people and organizations generously donating their time, resources, or expertise. CER invites you to join them in protecting culture in crisis. More information on how to support here: https://www.culturalemergency.org/support-us